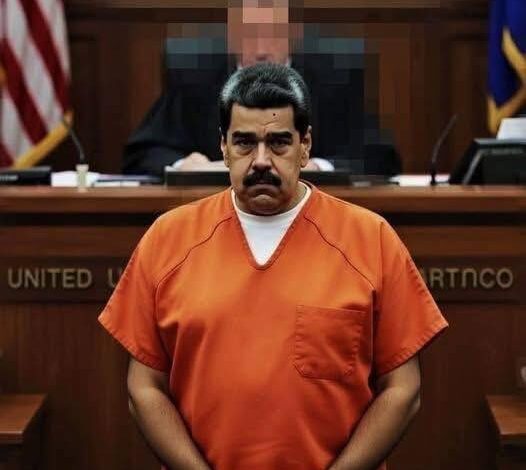

The halls of the United States Senate have become the primary battleground for a profound constitutional struggle, ignited by a high-stakes military operation in Venezuela that has fundamentally challenged the traditional boundaries of executive authority. Following the daring overnight capture of Nicolás Maduro by U.S. forces, Washington finds itself deeply divided over the legal and ethical implications of the raid. What was initially presented by the Trump administration as a targeted law-enforcement action has rapidly transformed into an existential debate over presidential war powers, congressional oversight, and the very definition of “hostilities” in the twenty-first century.

The operation itself was a masterclass in military precision but a lightning rod for legal controversy. In early January, elite U.S. units conducted a lightning strike in Caracas, apprehending Maduro and his wife before extracting them to New York to face long-standing narcotics and corruption charges. While the White House was quick to frame the event as the apprehension of an indicted criminal, the scale of the deployment—involving advanced aircraft, special operations forces, and a breach of foreign sovereignty—struck many as a quintessential act of war. Critics across the political spectrum were immediate in their condemnation, not necessarily of the objective, but of the process. They argued that by bypassing the legislative branch, the presidency had effectively staged a regime change under the guise of a police warrant.

This friction culminated in a dramatic legislative showdown centered on a War Powers Resolution. Sponsored by a bipartisan coalition including Senators Tim Kaine and Rand Paul, the measure sought to reclaim congressional territory by mandating that any further military engagement or deployment of forces in Venezuela receive explicit legislative authorization. The debate on the Senate floor was charged with historical gravity, as lawmakers wrestled with the precedent this operation set. Senator Rand Paul was particularly vocal, asserting that the removal of a foreign head of state through military force is inherently an act of war, regardless of the target’s criminal record. Senator Kaine echoed this sentiment, famously remarking that the administration’s “law enforcement” label failed to pass the “laugh test” given the geopolitical magnitude of the fallout.

The tension reached a fever pitch on January 14, when the Senate moved to vote on the resolution. In a moment of high political drama, a handful of Republican senators who had initially signaled support for the measure withdrew their backing following intense pressure from the White House. This pivot resulted in a 50-50 deadlock, which was ultimately broken by Vice President J.D. Vance. By casting the tie-breaking vote to block the resolution, the Vice President ensured that the administration retained its unilateral freedom of movement in the region, at least for the time being. However, the narrowness of the defeat served only to underscore the widening rift between the executive and legislative branches.

Defenders of the administration’s actions maintain that the operation was a surgical strike against a fugitive from justice, not an invasion. They argue that because no permanent U.S. troops remain on Venezuelan soil and no formal state of war exists with a sovereign entity, the War Powers Act of 1973 does not apply. To the White House and its supporters, Maduro was a narco-terrorist whose presence represented a clear and present danger to American interests, justifying a swift executive response. They contend that requiring a lengthy congressional debate for a sensitive extraction mission would have compromised the safety of the operatives and allowed the target to flee.

Beyond the domestic legalities, the capture of Maduro has sent shockwaves through the international community, raising urgent questions about global norms and the U.N. Charter. Legal scholars at institutions such as Chatham House have warned that the forcible removal of a sitting leader without the blessing of the United Nations Security Council could erode established international laws regarding the use of force. There is a palpable fear among diplomats that this “New York extraction” model could provide a blueprint for other nations to justify their own cross-border interventions under the pretext of criminal justice.

The regional fallout has been equally volatile. In Havana, tens of thousands of protestors gathered outside the U.S. Embassy, demonstrating against what they viewed as a return to “gunboat diplomacy” in Latin America. The intervention has strained ties with traditional regional partners who, while no friends of Maduro, are wary of any precedent that allows for the unilateral removal of a neighboring head of state. Conversely, within Venezuela, the political landscape is being radically reordered. CIA Director John Ratcliffe’s recent journey to Caracas to meet with acting President Delcy Rodríguez signals a pragmatic, if controversial, effort by the U.S. to stabilize the new interim government and secure its own influence in the post-Maduro era.

The complexities of this new era were perhaps best captured by a symbolic meeting at the White House between President Donald Trump and María Corina Machado. Machado, a prominent opposition figure and Nobel Peace Prize laureate, presented her medal to Trump as a gesture of gratitude for his role in Maduro’s ouster. While celebrated by the administration’s supporters as a triumph of liberty, the gesture was seen by critics as an unsettling fusion of Nobel-level resistance with unilateral military intervention. It highlighted the deep ideological fractures that the operation has exposed, both in Washington and abroad.

As the dust settles from the initial raid, the legislative struggle is far from over. Members of the House of Representatives are already preparing their own versions of the War Powers Resolution, and constitutional scholars are readying challenges that may eventually reach the Supreme Court. The core of the issue remains the same: in an age of precision strikes and hybrid warfare, where do police powers end and war powers begin? If the president can order the capture of a foreign leader without consulting Congress, the traditional checks and balances of American governance may be entering a period of permanent obsolescence.

The Maduro operation will likely be remembered as a turning point in American foreign policy and constitutional law. It has forced a reckoning over the Commander-in-Chief’s ability to act as a global enforcer and has pushed the Senate into a defensive posture, fighting to maintain its relevance in an era of executive dominance. Whether this leads to a formal redefinition of the War Powers Act or a permanent shift toward unilateralism is yet to be seen. For now, Washington remains a house divided, grappling with the reality that while the capture of a dictator may be a tactical victory, the cost to the constitutional order could be an enduring casualty. The debate in the Capitol is no longer just about the fate of Venezuela, but about the future of the American republic and the limits of the power concentrated in the Oval Office.